Egypt’s Unexplained Files

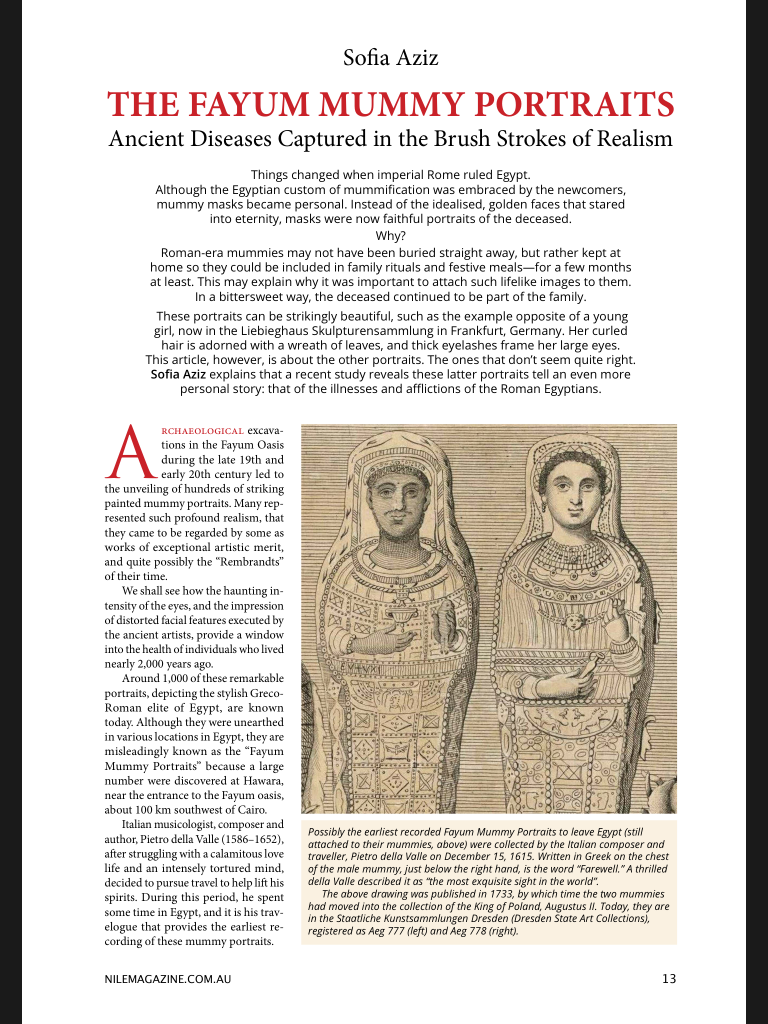

The Fayum Mummy Portraits: Ancient Diseases Captured in the Brush Strokes of Realism

Archaeological excavations in the Fayum during the late 19th and early 20th century led to the unveiling of several striking painted mummy portraits, representing such profound realism, that they came to be regarded by some as works of exceptional artistic merit and quite possibly the “Rembrandts” of their time. We shall see how the haunting intensity of the eyes, and the impression of distorted facial features executed by the ancient artists, provide a window into the health of individuals that lived nearly 2000 years ago.

To read my article in full please follow the link below:

https://www.nilemagazine.com.au/

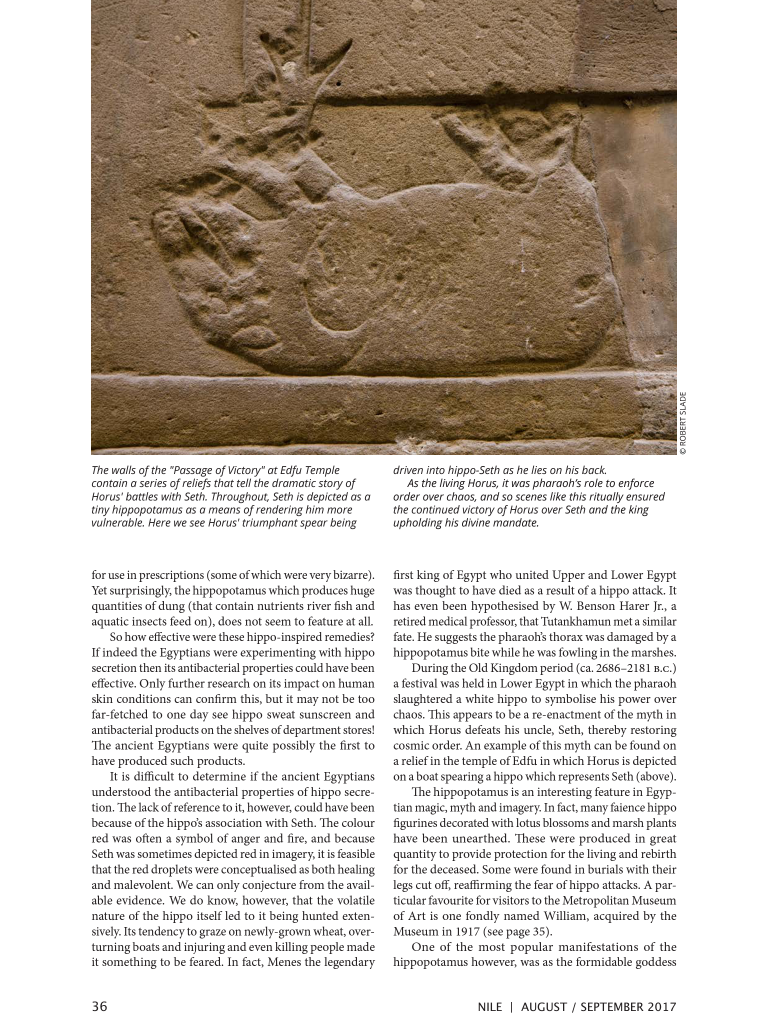

The Hippo In Egyptian Medicine and Magic

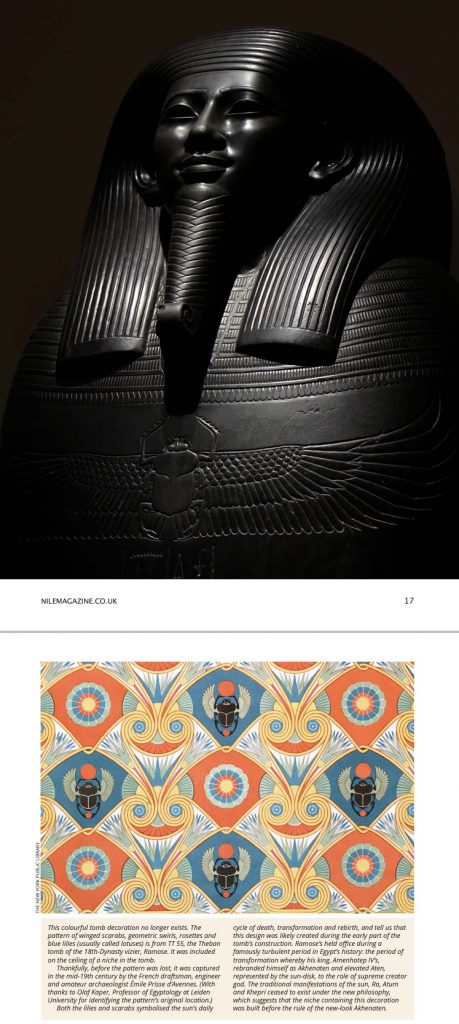

Celestial Scarab

What is it about the humble looking dung beetle that led the ancient Egyptians to venerate it and even use it in medicine? Looks are certainly deceptive when it comes to the dung beetle. Far from being humble, this species of beetle is extraordinary. Not only can it survive in a challenging, inhospitable terrain but it is also the strongest insect/animal in the world.

This beetle is found in the Egyptian desert, grasslands and farms. It depends entirely on dung for food and to cater for its offspring and therefore has to cope with debilitating heat radiating from the desert which could bake the beetle alive. But how does the dung beetle roll the dung ball in a straight line with a reverse ball pushing technique which obscures its vision? The beetle begins by climbing atop its sphere and performing a rotating dance. Remarkably, this dance is actually a rhythmic orientation movement which helps the beetle navigate itself using celestial cues. Scientists at Sweden’s Lund University have discovered that this small insect takes a “snapshot” of the sun, moon and stars to steer its dung home. Humans and birds are known to navigate by the stars but this could be the first example of an insect doing so.

Were the ancient Egyptians aware of the solar/celestial navigational skills of the beetle? Interestingly, the dung beetle was linked to solar worship in ancient Egypt. The sun was conceptualised as a principal force, which manifested itself in various guises in a daily struggle for existence. The god Khepri was depicted as a scarab beetle or a man with the head of a scarab, and symbolised the sun in the morning, appearing as a huge celestial beetle propelling the sun above the horizon in imitation of it rolling a dung ball through the sand. The verb kheper translates as “to become” or “to come into being”, and in Egyptian myth, the scarab came to represent the ability of the sun god to bring about his own rebirth. The noun “scarab”, kheperer means “that which comes into being”literally. Such representations can be seen in the scarab’s multiple depictions in the amduat “that which is in the netherworld”—a New Kingdom text describing the sun’s nocturnal wandering through the shady world of the Egyptian afterlife, and subsequent self-resurrection. At nightfall, Ra descended into the underworld in his night boat, crowded with deities, protective demons and spirits of the blessed dead.

The best-known scarab of all is the heart scarab. This is a large amulet of hard green or black stone, placed over the heart of the mummy and inscribed with Chapter 30B from the Book of the Dead, whereby the deceased implores his heart to not mess up his chances at a blissful afterlife: “O my heart, which I had from my mother, the centre of my being. Do not stand against me as a witness, do not oppose me in the judgement hall, in the presence of the keeper of the balance.”

While the scarab could help provide a happy afterlife, the Egyptians were well aware that foodstuffs placed inside tombs—as well as embalmed corpses—were attractive targets for all manner of insects. Insects preying on the deceased’s body were a big danger to a happy ever after. Beetles form the largest single group of insect species, and one particular chapter of the Book of the Dead was written to try and deal with the problem. Spell 36 contains an incantation to repel a beetle: “Begone from me, O Crooked-lips!” The term “crooked lips” likely refers to the clypeus—the broad plate at the front of the beetle’s head (scarabs use it to efficiently shovel dung).

Scarabs grew in popularity and continued to be produced in the millions for use as beads, pendants, seals and in rings until the fourth century a.d. Their amuletic properties led to a vast array of magical hieroglyphic symbols appearing on the base. The scarab beetle was even included in the various medical and magical papyri. The Ebers Papyrus is named for the German Egyptologist Georg Ebers, who purchased the papyrus scroll in Luxor in the winter of 1872. Thought to date from around the reign of Amenhotep I (ca. 1525 b.c.), the Ebers Papyrus contains a recipe to eliminate bewitchment in which the head and wings of a scarab are scorched, mixed with some salamander fat, heated and then drunk.

Scarabs continued to be used in magic spells long after the death of Cleopatra in 30 b.c. and Egypt’s assimilation into the Roman Empire. The Demotic Magical Papyrus of London and Leiden was written in the 3rd century a.d. contains a fascinating “love potion” designed to seduce a woman, and features a type of scarab wine: “[The method] of the scarab of the cup of wine, to make a woman love a man. You take a fish-faced scarab…. You take it at the rising of the sun… and you address it before the sun when it is about to rise, seven times. … When evening comes, you take it out, you spread its under part with sand, and put a circular strip of cloth under it upon the sand, unto four days…. When the four days have passed, and it is dry…. you divide it down its middle with a bronze knife …. [With one half] make it into a ball and put it in the wine, and speak over it seven times, and you make the woman drink it….”

The magic formula continues at some length and describes how to bind the other half of the scarab mixture to one’s left arm whenever one wants to “lie with a woman”. What’s interesting is how it incorporates the solar aspects of the scarab beetle within the spell.

In the mesmerising western desert of Egypt, not only does the scarab have the skills to survive the lethal heat, but within the landscape of the legendary singing dunes it emerges to life from within a dung ball—a ball which was remarkably pushed in a straight line after performing an orientation dance. While it’s unlikely the ancient Egyptians fully understood the scarab’s unique skills in using the Milky Way to navigate itself home, the beetle’s “magical” self-reproduction and physical strength made it not just an ideal celestial/solar deity, but also the most popular amulet in Egyptian history.

An excerpt from my article in Nile Magazine #14. To read more:

https://www.nilemagazine.com.au

An Examination of the Death of Cleopatra and the Serpent in Myth, Magic and Medicine

From the dawn of civilisation, the snake has been synonymous with various ideological representations of chaos, malevolence, protection and healing in almost every culture across the globe. In Egyptian society the serpent played a magical role within the realms of healing: both apotropaic (turning away harm) and prophylactic (safeguarding from harm). Yet the snake was also conceptualised as an evil entity in the form of Apep who was monstrous and the embodiment of disorder. Consequently, numerous spells were included in texts of tombs to ward off the evil serpents that densely populated the duat or netherworld. The most iconic and popular representation of the snake, however, remains in the narrative of the tragic death of one of Egypt’s most famous queens, Cleopatra VII.

The date was August 12, 30 B.C. and it set in motion one of history’s most epic stories—even providing inspiration for Shakespeare, whose Antony and Cleopatra was first performed in London about 1606. An intriguing story of lust, power, deceit, incest, murder and suicide; ending in one of the greatest unsolved mysteries in history: how did Queen Cleopatra die?

The ancient writers give us a glimpse into Cleopatra’s extraordinary life and psyche concluding with various accounts of her tragic demise. Suicide is the common theme in all the narratives and all concur that two of her handmaidens died with her. Strabo provides the earliest account and is the only source that could have been in Alexandria at the time of her death. He mentions two possibilities; that of the venom of a snake or a poisonous ointment. Galen refers to a belief that she bit herself and poured snake poison into the wound. Dio Cassius states the only marks on her body were slight pricks on her arm implicating a snake as the culprit, which could have been brought to her in a watering jar or among flowers. The most famous account by far, however, remains Plutarch’s and it is his explanation which has managed to survive the test of time.

Plutarch tells us her death was very sudden. A snake was carried into her with figs by an Egyptian peasant, and lay hidden under the leaves in his basket. Cleopatra had given orders that the snake should settle on her without her being aware of it and baring her arm, she held it out to be bitten. He offers an alternative possibility of poison being concealed in a hollow comb she kept in her hair. Interestingly, Plutarch tells us that there were no marks on her body or physical signs of poisoning. The snake was also nowhere to be seen apart from some fresh tracks indicating its earlier presence.

In 2015 academics at the University of Manchester reopened the discussion on Plutarch’s account and argued that the cobra in question would have been too large a species (typically 5-6ft long) for concealment in a basket of figs. Furthermore, herpetologist, Andrew Gray explained that there was just a 10% chance of death since most bites are dry bites that don’t inject venom. So why has the snake story prevailed? Plutarch was not an eyewitness and writes around 150 years after Cleopatra’s death. In order to unravel this mystery we need to take a closer look at the serpent in Egyptian myth, magic and medicine. This is significant because Cleopatra represented herself as the reincarnation of Isis, a goddess of magic and healing and the consort of Osiris.

How plausible is Plutarch’s claim? Cleopatra’s fascination with medicine is documented by some writers and there is even a suggestion she wrote a treatise on cosmetics. Whether or not she actually wrote the treatise is questionable because much of what is stated to be included in it was already available in the Ebers papyrus which predates Cleopatra. Some interest in medicine and cosmetics however, is evident from her lifestyle and her physician Olympus was very much part of her inner circle. Plutarch’s claim of her interest in snake venom is also plausible. What knowledge did the ancient Egyptians have of ophiology though?

The best example of this can be found in the Brooklyn papyrus numbers 47.218.48 and 47.218.85. This artefact is in the Brooklyn Museum and dates to the early Ptolemaic period but the original is thought to be from a much earlier period. The papyrus was a manual for medico-magical practitioners (Serqet priests) who may have been called upon to deal with snake bite victims. The first part of the papyrus lists twenty one snakes although it is thought that it may originally have listed thirty seven. Some identification with snakes of our modern day world was made by the French scholar Serge Sauneron who translated the papyrus into French. John F. Nunn (1996) consulted with Professor Warrell at Oxford regarding identification. In some instances he concurred with Sauneron and in others made a different identification. As a result we have a list of the possible species identified by the ancient Egyptians. These include the spitting cobra, hooded malpolon, black dessert cobra, Persian horned viper, sand boa, puff adder and the Egyptian cobra (Naja Haje) which is implicated in the death of Cleopatra.

To read more : https://www.academia.edu/36915262/An_Examination_of_the_Death_of_Cleopatra_and_the_Serpent_in_Myth_Magic_and_Medicine

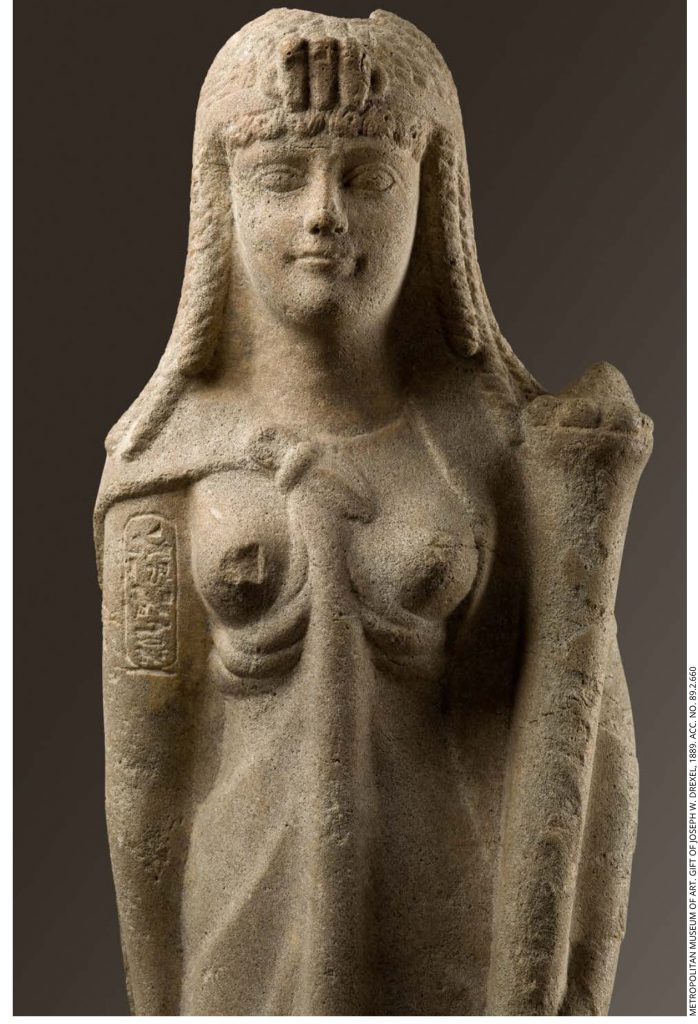

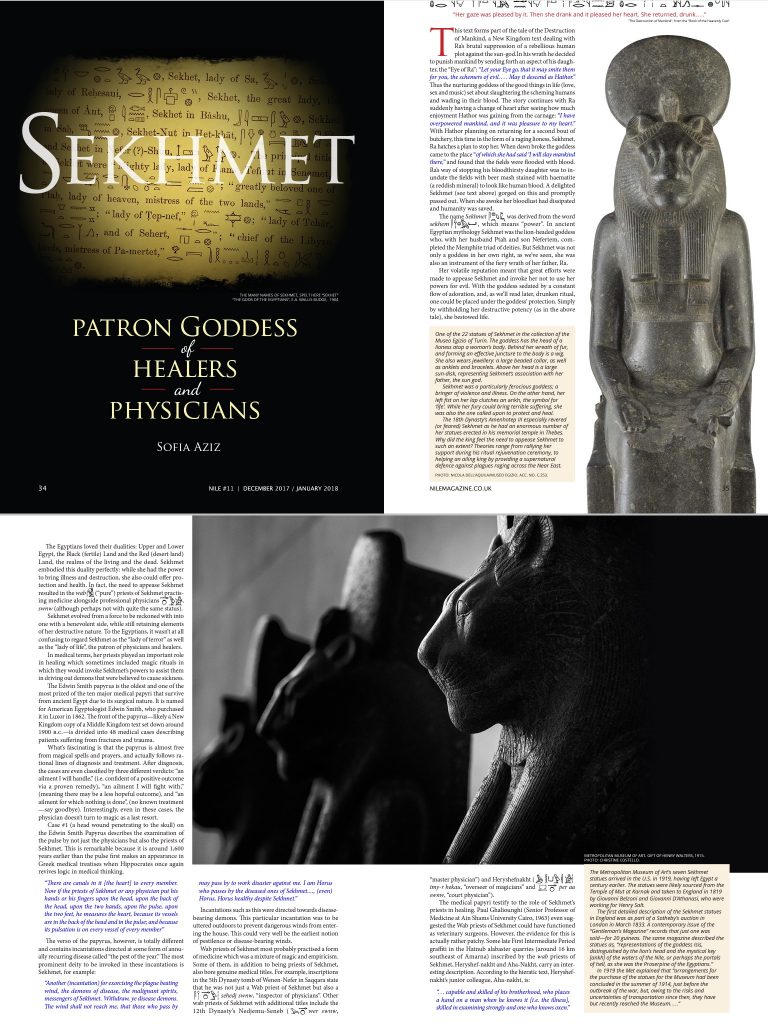

Sekhmet- Patron Goddess of Healers and Physicians

Available for free download:

https://www.academia.edu/36934248/Sekhmet-_Patron_Goddess_of_Healers_and_Physicians

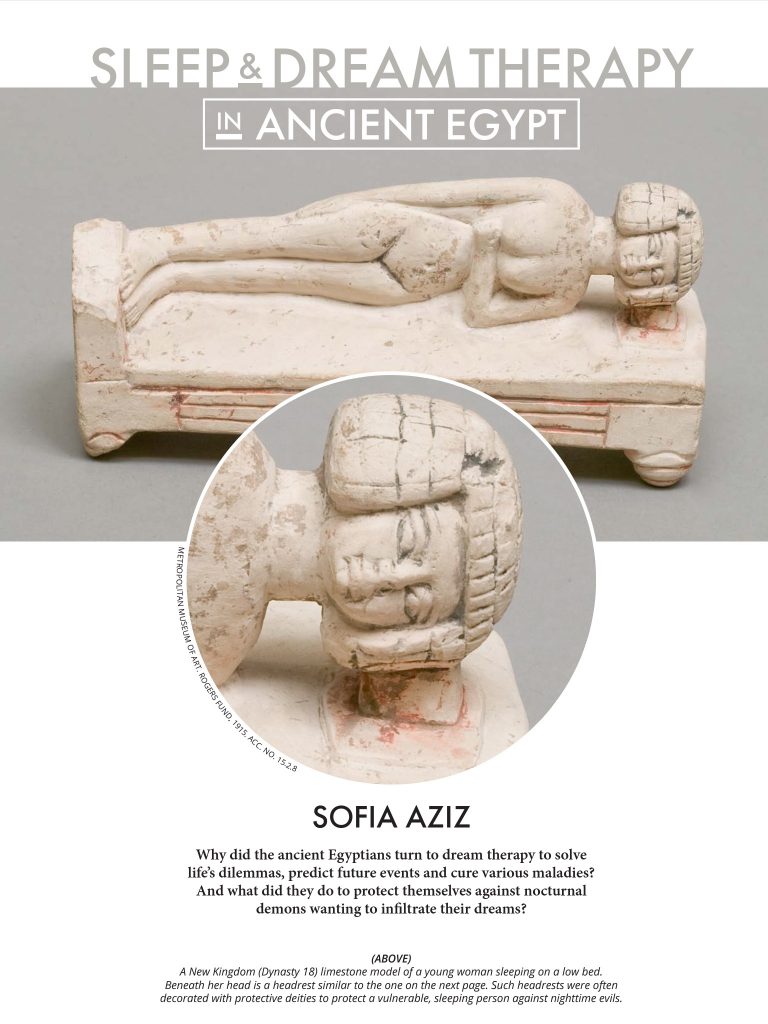

Why did the ancient Egyptians turn to dream therapy to solve life’s dilemmas, predict future events and cure various maladies? And what did they do to protect themselves against nocturnal demons wanting to infiltrate their dreams?

Sleep is a universal phenomenon that unites all animals and has always been a core aspect of our existence, yet the function of sleep remains a scientific conundrum that is still being unravelled. For the ancient Egyptians, oneiromancy, i.e. the interpretation of dreams provided hidden messages about a person’s future, and dream therapy was used to assist in healing numerous afflictions. At temples such as Dendera, patients experienced therapeutic dreaming that magically facilitated an encounter with the gods. The hoped-for outcome was divine intervention to relieve the patient from a medical affliction. But what exactly is sleep and why have dreams always been an area of fascination for humans?

Medically speaking, sleep is both a perplexing and bizarre phenomena which causes bouts of unconsciousness in which paralysis occurs, muscles twitch involuntarily and the eyes dart back and forth. Irregular breathing and heart rate is accompanied with hallucinations, hearing voices and seeing things that aren’t there. It all sounds rather alarming. These hallucinations can be terrifying at times, and although we understand them as nightmares, it is likely they were responsible for early myths about demonic beings and life after death.

Dreams connect us with the deepest and darkest part of ourselves and help us engage with our unconscious selves. Sigmund Freud believed dreams were messages from our unconscious mind, while Karl Jung proposed that dreams tap into a vast collective unconsciousness of shared human memory. Hippocrates, the father of medicine, postulated that dreams could reveal cures for illnesses, and the ancient Egyptians believed dreams emanated from external forces such as the gods, demons or the dead.

Modern day neuroscience studies are demonstrating that what we observe is not merely a passive reception of information but rather a reality created by our brain; dreams are more than the random firing of synapses and are vital for our health and wellbeing and play an important role in cognitive development and consolidating memory.

My article on sleep and dream therapy is available now:

https://www.nilemagazine.com.au

https://www.academia.edu/41809343/Sleep_and_Dream_Therapy_in_Ancient_Egypt

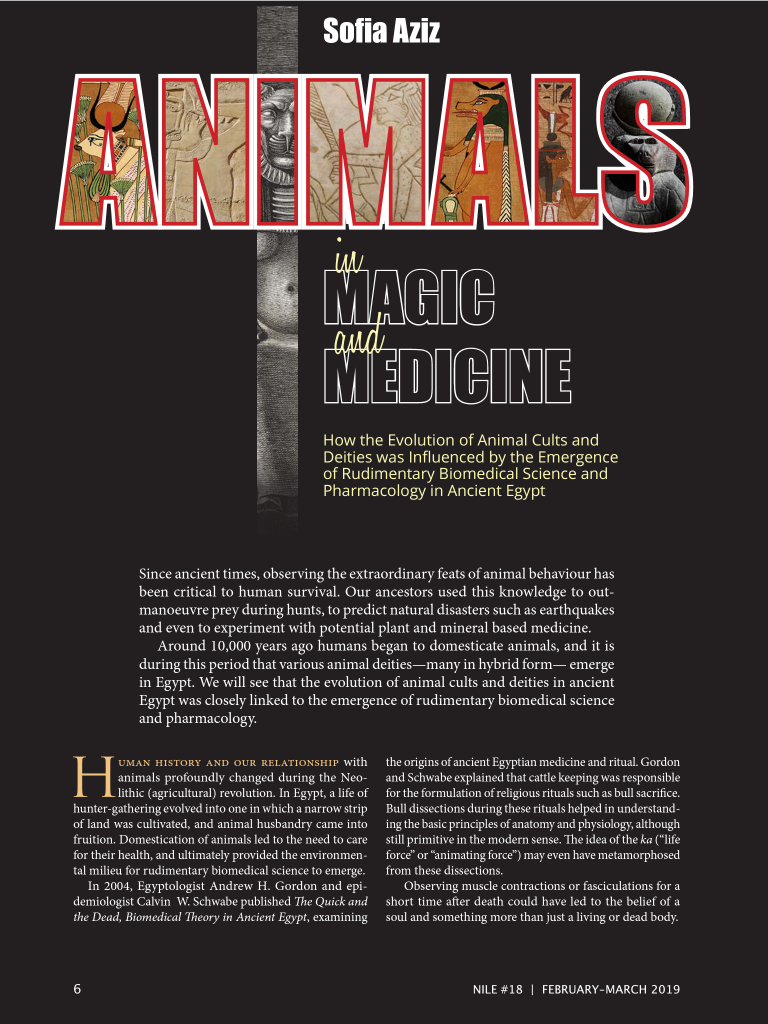

How the Evolution of Animal Cults and Deities was Influenced by the Emergence of Rudimentary Biomedical Science and Pharmacology in Ancient Egypt

Since ancient times, observing the extraordinary feats of animal behaviour has been critical to human survival. Our ancestors used this knowledge to out manoeuvre prey during hunts, to predict natural disasters such as earthquakes and even to experiment with potential plant and mineral based medicine. Around 10,000 years ago humans began to domesticate animals and it is during this period that various animal deities, many in hybrid form emerge in Egypt. We will see that the evolution of animal cults and deities, in ancient Egypt, was closely linked to the emergence of rudimentary biomedical science and pharmacology.

Human history and our relationship with animals profoundly changed during the Neolithic (agricultural) revolution. In Egypt a life of hunter gathering evolved into one in which a narrow strip of land was cultivated and animal husbandry came into fruition. Domestication of animals led to the need to care for their health thus providing the environmental milieu for rudimentary biomedical science to emerge. Gordon and Schwabe in their book ‘The Quick and the Dead, Biomedical Theory in Ancient Egypt, 2004’ explain that cattle keeping was responsible for the formulation of religious rituals such as bull sacrifice. Bull dissections during these rituals helped in understanding the basic principles of anatomy and physiology, although still primitive in the modern sense. The idea of the ‘ka’ (soul/spirit) may even have metamorphosed from these dissections. Observing muscle contractions or fasciculations for a short time after death, according to Gordon and Schwabe, could have led to the belief of a soul and something more than just a living or dead body. They elaborate on this theory by stressing the bull’s forelimb was the first to be removed, and in a state of muscle spasm was hurriedly used in the opening of the mouth ceremony as part of the revivification ritual. They provide several examples in support of this theory including an inscription in the sixth dynasty tomb of Khentika: ‘Let the foreleg come away, hurry up.’ Ka incidentally was also the name for bull and Gordon and Schwabe, think it likely, that the ka sign signifies the bull’s two horns. The bull could even be one of the earliest animals to be associated with divinity in ancient Egypt. The Apis bull, recognised by specific markings, became hugely important in the Memphis region and its cult emerged as early as the first dynasty, although the ideological representations of it as a divinity probably began earlier.

But what is a less known intriguing fact about some animals is their remarkable ability to self medicate and how observing this could have led humans to turn to nature’s pharmacy for health care. This is a fascinating area of research and even the esteemed Naturalist and Broadcaster Sir David Attenborough has appeared in several documentaries which have filmed animals in the wild self medicating by using plants to cure a number of ailments. Animals such as capuchin monkeys have even been observed manically rubbing pungent plants all over themselves; incredibly, the pungent chemical repels insects and keeps the animals free from unpleasant bites. Our ancestors witnessed this extraordinary behaviour and documented accounts of animals self medicating survive from ancient Greece and Rome. Living in settlements with a growing population meant disease and death was rampant therefore discovering the medicinal use of plants and minerals was a major breakthrough for early societies. The Egyptian pharmacopoeia came to consist of drugs of mineral and vegetable origin. Minerals such as clay, copper, granite, gypsum, lapis lazuli, Nile mud, and natron were utilised and herbal remedies, for instance, included acacia, coriander, date, hemp, juniper, linseed, moringa, onion, willow and wormwood. Incantations and spells invoking the assistance of a number of gods were also included in the medical papyri.

Nile Magazine #18 Feb-March 2019 to read more of my article.